The company has applied for EU state aid for the funding under the EU’s Important Projects of Common European Interests (IPCEI) programme.

“Microelectronics is the future and is vital to the success of all areas of Bosch business,” says chairman Stefan Hartung, “with it, we hold a master key to tomorrow’s mobility, the internet of things, and to what we at Bosch call technology that is ‘Invented for life’.”

The semiconductor centre in Reutlingen is being systematically expanded: between now and 2025, Bosch is to invest around €400 million in the expansion of manufacturing capacity and the conversion of existing factory space into new clean-room space.

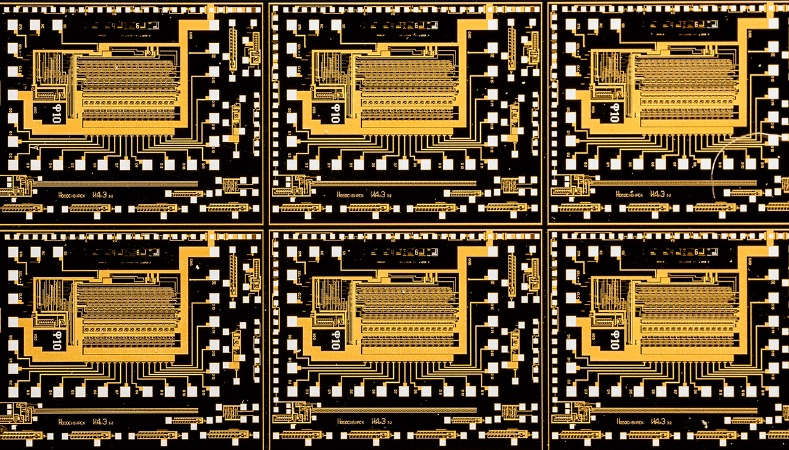

This includes construction of a new extension in Reutlingen, which will create an additional 3,600 square meters of clean-room space. Reutlingen is Bosch’s SiC production facility.

Clean-room space in Reutlingen is set to grow from around 35,000 square meters at present to over 44,000 square meters by the end of 2025.

€250 million will be spent on adding 3,000 sq m to the clean-room at the €1 billion Dresden fab it opened last year.

“We’re gearing up for continued growth in demand for semiconductors – also for the benefit of our customers,” says Hartung, “for us, these miniature components mean big business.”

“Europe can and must capitalise on its own strengths in the semiconductor industry,” adds Hartung “more than ever, the goal must be to produce chips for the specific needs of European industry. And that means not only chips at the bottom end of the nanoscale.”

Bosch is looking at processes between 40nm and 200nm.

Bosch says its expanded capabilities will enable production of radar ICs for automotive, MEMS sensors on 300mm wafers, and miniature projection modules for spectacles.

“Production is scheduled to start in 2026” says Hartung, “our new wafer fab gives us the opportunity to scale production – an advantage we intend to exploit to the full.”

“We’re also looking into the development of chips based on gallium nitride for electromobility applications,” adds Hartung, “these chips are already found in laptop and smartphone chargers.”

Before they can be used in vehicles, they will have to become more robust and able to withstand substantially higher voltages of up to 1,200 volts.

“Challenges like these are all part of the job for Bosch engineers,” says Hartung, “our strength is that we’ve been familiar with microelectronics for a long time – and we know our way around cars just as well.”