S. Himmelstein | June 15, 2023

Thwaites Glacier represents potential to dramatically raise global sea levels as the world warms. Source: NASA

Thwaites Glacier represents potential to dramatically raise global sea levels as the world warms. Source: NASA

The loss of glacial ice is accelerating, portending an ominous future for sea level stability due to anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. Antarctica is losing ice mass via melting at an average rate of about 150 billion tons per year, and Greenland is losing about 270 billion tons per year, adding to sea level rise, according to data from NASA.

The ice sheets in these regions store about two-thirds of all the fresh water on Earth and are losing ice due to the ongoing global warming. Meltwater derived from the ice sheets is responsible for about one-third of the global average rise in sea level since 1993. The implications of such trends for the future of the Greenland ice sheet and the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica were the focus of recent research.

The Thwaites Glacier

An 80-mile-wide stream of sliding ice at the heart of Thwaites Glacier in Western Antarctica is projected to creep outward over the next 20 years and speed up ice loss. Field observations and modeling studies conducted by researchers from Stanford University and the University of Waterloo, Canada, indicate the glacier could drop billions of tons of ice into the Amundsen Sea and open a path for more inland ice to flow freely to the coast.

The observed thinning of Thwaites Glacier, together with changes in the slope of its surface and the conditions at its base, makes both sides prone to move a few miles outward over the next 20 years. Modeling research reported in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface shows the glacier’s eastern shear margin to be most susceptible to migrating away from the main trunk, and the western boundary appears prone to widening as well.

Ice loss from this glacier currently contributes around 4% of all global sea-level rise (assuming 3.5 mm annual sea-level rise) and has the potential to contribute significantly more.

The Greenland ice sheet

Loss of the Greenland ice sheet, which covers 660,200 square miles in the Arctic, would raise global sea level about 23 ft, but scientists aren’t sure how quickly the ice sheet could melt. This ice sheet is already melting; between 2003 and 2016, it lost about 255 gigatons (billions of tons) of ice each year.

[Stay abreast of this hot topic with a free subscription to the Environmental Technology newsletter from GlobalSpec]

Modeling tipping points, which are critical thresholds where a system behavior irreversibly changes, helps determine when that melt might occur. Prospects for this occurrence were studied by researchers from Potsdam-Institute for Climate Impact Research (Germany) and GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences and published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

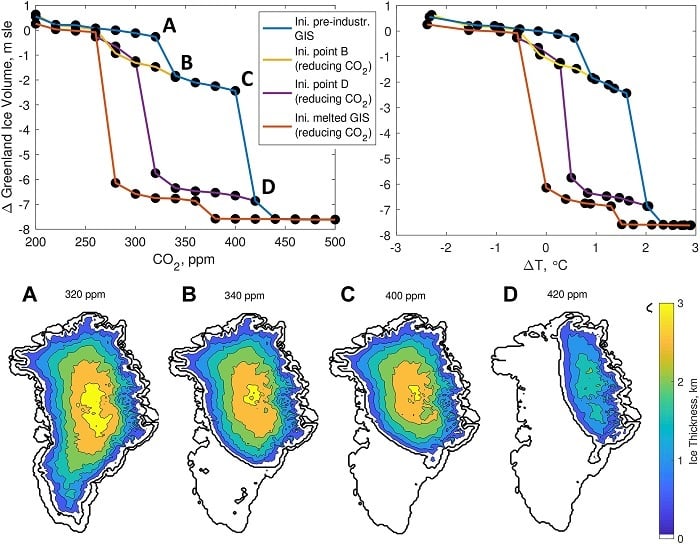

Equilibrium states of the volume of the Greenland ice sheet (black dots) with respect to pre-industrial data as a function of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (top left) and corresponding temperature anomaly (top right). The blue curve denotes increasing carbon dioxide concentration starting from the pre-industrial era. The other curves reflect decreasing carbon dioxide starting from a completely ice-free condition (red curve) and from intermediate states (yellow and purple curves), respectively. The bottom panel illustrates the ice sheet thickness at the points A–D. Source: Geophysical Research Letters (2023). DOI: 10.1029/2022GL101827

Equilibrium states of the volume of the Greenland ice sheet (black dots) with respect to pre-industrial data as a function of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (top left) and corresponding temperature anomaly (top right). The blue curve denotes increasing carbon dioxide concentration starting from the pre-industrial era. The other curves reflect decreasing carbon dioxide starting from a completely ice-free condition (red curve) and from intermediate states (yellow and purple curves), respectively. The bottom panel illustrates the ice sheet thickness at the points A–D. Source: Geophysical Research Letters (2023). DOI: 10.1029/2022GL101827

Simulations with constant temperatures were performed to define equilibrium states of the ice sheet — points where ice loss equaled ice gain. Subsequent modeling of a set of 20,000-year-long simulations with carbon emissions ranging up to 4,000 gigatons of carbon revealed a 1,000 gigaton carbon tipping point for the loss of the southern portion of the ice sheet. A sea level increase of 6.9 m is predicted as the entire ice sheet disappears if the 2,500 gigaton carbon tipping point is reached.

About 500 gigatons of carbon have already been emitted — halfway to the first tipping point.

“We cannot continue carbon emissions at the same rate for much longer without risking crossing the tipping points,” said the researchers. “Most of the ice sheet melting won’t occur in the next decade, but it won’t be too long before we will not be able to work against it anymore.”